The three poets

| Three poets on poetry, friendship, and claims to a vanishing place. | ||

1. Naushad Noori

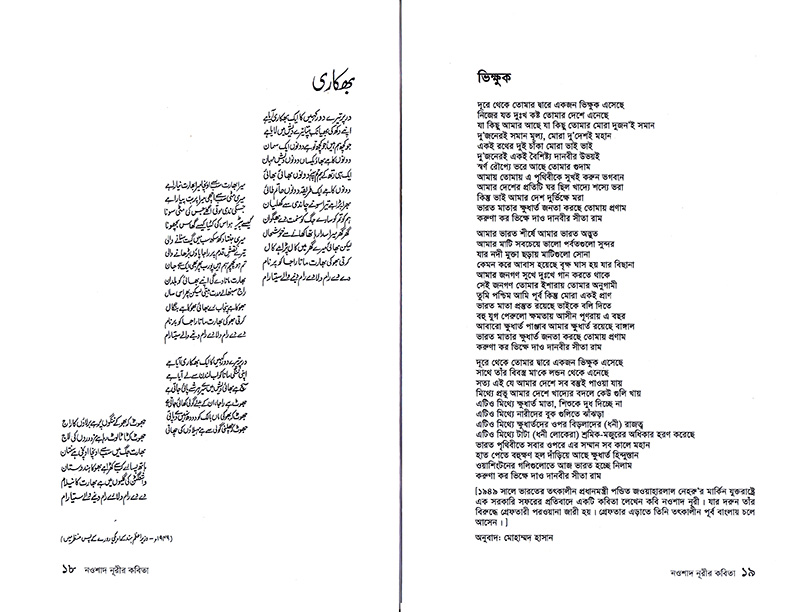

Naushad Noori was a pen name. He was born Mohammad Mustafa Masum Hashmi in October of 1926 to Advocate Abdul Kafi Hashmi and Owaisa Bibi in Darbhanga, Basantpur, Bihar. In poetry and politics, his twin calling, Noori hewed closely to his left leanings, joining both the United Front and Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani’s National Awami Party (NAP) and becoming an active member of both parties. In a volume of his collected works, Mononrekha, Saiful Islam Saif describes Noori as a “poet to the deprived,” and his contemporaries remember him as a standard bearer of Urdu literary societies in Bangladesh. Noori wrote copiously and with heart, unrelenting in a left internationalist ethos.

"My father, he was a bohemian type,” reminisces Haikal Hashmi. “Most days he came home around midnight and immediately woke us up because he usually always brought something for us, and after feeding them to us, instructed us then to promptly return to bed – so jao, so jao, so jaoGo to bed, go to bed. – this was the total peculiar life. We got to spend more time with him 1978-79 onwards. He was a Communist Party sympathizer but the Party was banned in Pakistan amol, so they had to find work arounds, he became a NAP member. He published a magazine called ‘Rudad’ for NAP; their offices were in Motijheel Zohra Mansion. Ahmed Ilias (the poet) chacha also worked there. Later from 1969 until March of 1971 they were involved with another magazine called “Zarida” sympathetic to the Bengali self-determination struggle. In March 71, the first Bangladeshi flag in Mirpur was raised at our house. In Yahya’s white paper, my father was identified as wayward. But soon we were evicted from our house. During the war we fled to Mohammadpur, to College Gate to an uncle’s house, and then to Ilias chacha’s house on Noorjahan Road.”

Noori, in Hashmi’s words in Mononrekha, was a foremost figure in the literary and political “Mohammadpur underground.” My father was a simple man. One time, as he was about to leave for medical treatment in Kolkata, he informed me he had some liabilities he would like to settle. With apprehension I asked who, how much and he said he owed a mango vendor at Town Hall Market 350 taka: “please ask Shamim (the poet and Noori’s friend Shamim Zamanvi) to get him the money” he said. At the age of 73 or 74, his total liability was only 350 taka! But he hardly got his salaries on time in his working days, we grew up with a lot of financial hardships. When Faiz Ahmad Faiz visited Bangladesh in 1974, he wanted to see my father. They were put up at Hotel Intercontinental and abba asked whether I wanted to go with him to see them and I said yes. There were also Malik Meraj Khalid and Mahmud Ali Kasuri in that delegation, the leftist group, so I went and when I saw Faiz I thought he didn’t look handsome, I was unimpressed, my young self completely unaware of his caliber as a poet.”

Photo by: Sushanta Kumar Paul

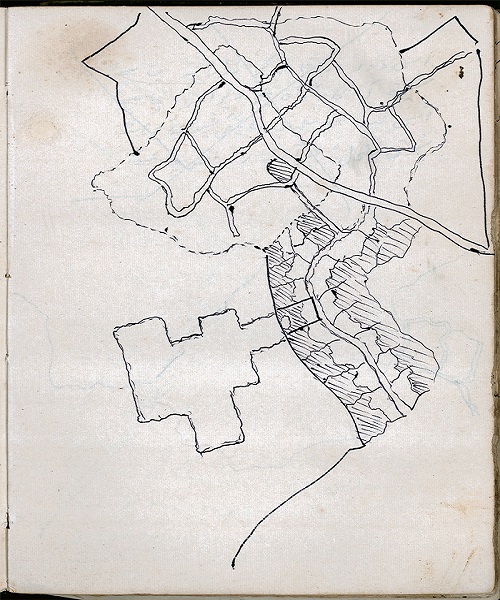

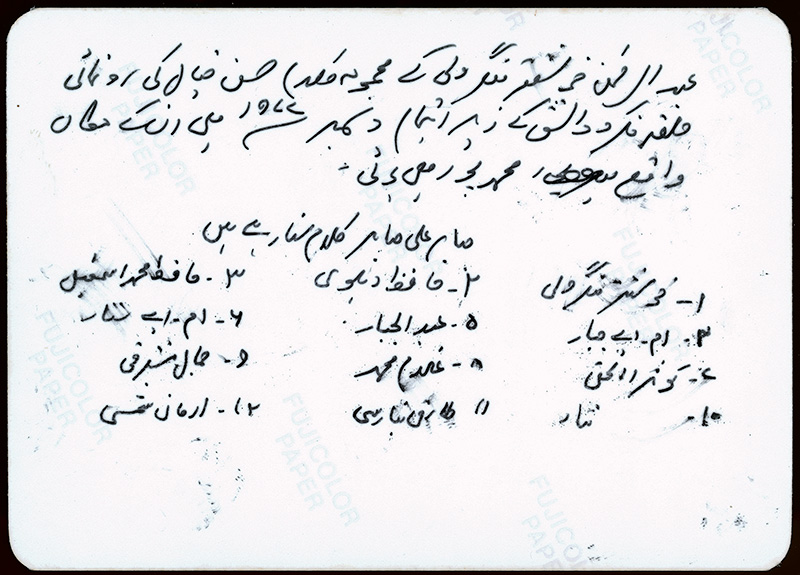

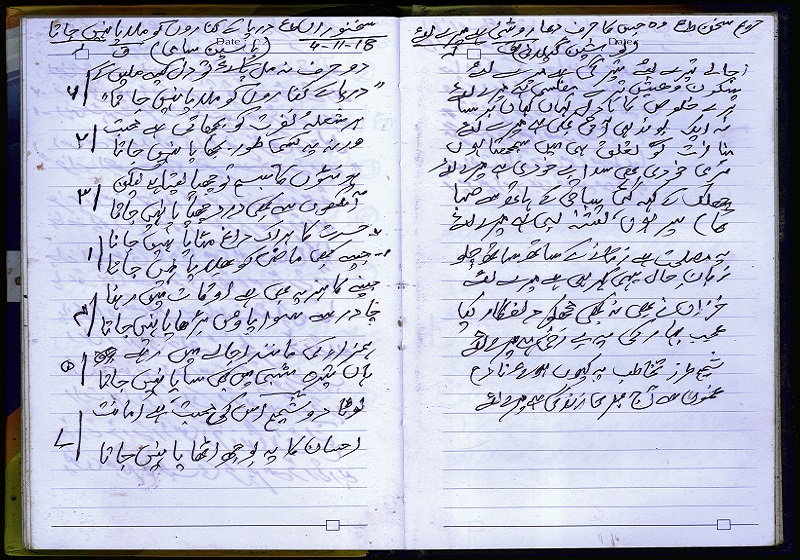

Ever the man of letters, Noori’s notebooks and photographs, preserved by his son, offer a glimpse of a meticulous mind: besides being a poet and political activist, Noori was an archivist of his milieu. Many of his photographs of mushairas and literary gatherings, for example, are inscribed with handwritten notes to identify the participants. The notebooks carry with them drafts and revisions – when a poem was ready for publication, he crossed it out – along with memories of mundanities of life. Stricken with cancer late in life, he used his notebooks to communicate with family members, writing everyday instructions for them in red. They have since been further annotated by Haikal Hashmi, as if a site of ongoing conversations.

2. Shamim Zamanvi

The poet Shamim Zamanvi made a home in his friendships. From Zamania to Khulna, Chattogram to Dhaka, the stories he is fond of sharing are of intimacies and kinship: "This is my home as my friends are here. In 2000 Ahmed Ilyas, Asad Chowdhury, and I went to India to launch a volume by Naushad Noori, Raho Rashme Ashnai. Then took an eight hour train to Zamania. My cousin – mamato bhai – now lives in our house. I am glad the house is still inhabited: daily baati joleThe lights are on everyday. . Back in 1975 I signed some court documents to formally transfer my rights to the house there. This is my home."

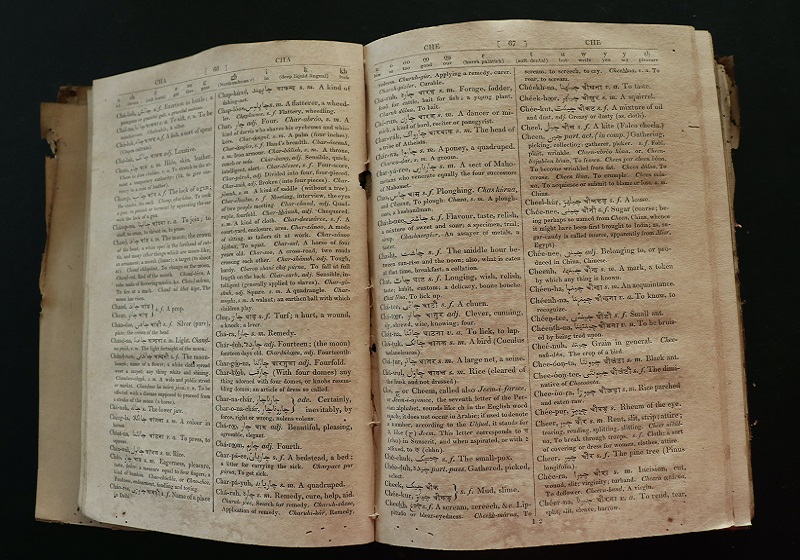

Zamanvi relocated to Mohammadpur in 1995 at the request of Naushad Noori and Ahmed Ilias to revive Dhaka’s Urdu poetry circles. If Naushad Noori was the guiding figure of Urdu literary spheres, Zamanvi is its beating heart, called by writer Javed Hussen, “one of the finest Urdu poets alive.” With an encyclopedic knowledge of Urdu poetry and a convivial spirit, Zamanvi manifests the joyous, interactive essence of mushairas, threading stories with warmth, wit, personalities, knowledge, and detail. A trip to India in the 1970s features a train ride with left leader Irfanullah Khan: “When the border agents boarded the train, Irfanullah became fearful and left my side to move to a different seat. Seeing the approaching guards, I took off my watch, and asked one of them in Purbi – ‘rawa ki ghari me kitna bajal ho?’What time is it? – they were surprised to hear me speak in the language and we struck up a conversation, even asked to say hello on our way back.” A late-night ride home from a mushaira is a brush with danger: “I was returning from a mushaira at Shabana’s house, Haikal’s (Hashmi) sister. We were on a rickshaw and I had with me a bag full of my books and notebooks. Suddenly someone pulled at the bag and before I realized anything, it was gone. I was so bereft I didn’t write for two years but the poet Asad Chowdhury said one day, ‘what’s gone is gone, you can’t mourn forever.’” Ask about his poetry and he offers these lines: “Ek roz tujhpe sau ilzam ayenge / Saki sekasta jaam ke tukre uthake raakh / Aiyame tashnangi mey kaam ayenge.”One day you will be defamed with myriads of accusations / O saki! Gather and store the shreds of the broken cup / They will be useful in the days of thirst.

Ghalib, Iqbal, and Faiz Ahmad Faiz are his favorite poets. “I like Faiz because he’s so versatile, so distinct, the way he illuminated the human spirit and condition is unrivalled. Take ‘gulon mein rang bhare baad-e-naubahaar chale’ famously sung by Mehdi Hassan, the verses resonate with so many moods and emotional registers, not just romantic love.”

Photo by: Sushanta Kumar Paul

In his 2014 memoir The World I Saw, Ahmed Ilias writes of Zamanvi: “After 1975, SM Sajid came to Dhaka and stayed with me as a paying guest. His arrival in Dhaka was followed by Shamim Zamanvi and Yawar Aman, both of whom moved to Dhaka from Khulna. With their arrivals, literary activities found a new momentum. Shamim Zamanvi knows the art and skill of organizing and conducting Urdu mushaira. For several years it was our routine to meet at Sajid’s room and chalk out our literary programs. At night Sajid, Shamim, and I used to have dinner together at Society Hotel at Thatari Bazar and after dinner visit Hafez Dehalvi at Lal Mohan Saha Street to continue our discussions of Urdu literature.” [lightly edited]

“Urdu,” Zamanvi says, “has no future here (in Bangladesh). The young generation isn’t even interested in learning the language,” a sentiment echoed by many and is more a testament to social-political contestations than individual aversion. But Zamanvi himself is unfazed and holds to Urdu’s rich tradition in Bengal. His notebooks have accumulated again; he writes almost daily, a few lines, some pages, adapting the back-and-forth of mushairas to social media, where he posts his poems regularly. “I started posting my poems to Facebook urged on by Ahmed Ilias who used to do the same. Soon,” Zamanvi reveals in a bit of friendly ribbing, “I was far ahead posting more frequently than him.”

3. Ahmed Ilias

“Dhaka was divided into two sections,” says Ahmed Ilias, the two sections reflecting the across the tracks ethos of bifurcated modern Dhaka. “Puran Dhaka was on one side of the rail line (the Kamalapur Railway Station) and on the other side, the new settlements and areas.” Born in Taltola, Kolkata, Ilias was a Kolkata scholarship student until partition ended his Kolkata funding. His scholarship was transferred to schools in East Pakistan and Ilias arrived in Dhaka funded by the Haji Mohsin Fund in order to study at an alia madrasa.

Photo by: Sushanta Kumar Paul

His studies stalled, though, and were punctured and punctuated by financial difficulties, a return to Kolkata and back, jobs of necessity – washing clothes at Arrow Tailors in Puran Dhaka, salesperson at Jamal and Brothers, a clothing accessory shop. “Jamal and Brothers was on 91 Nawabpur Road next to the Awami League office on 92 Nawabpur. Got to know Suhrawardy in those days. If he arrived before the office opened, he waited in our store and we spoke mainly about Calcutta days.” There was a bakery on Free School Street where Ilias worked: “They had a coupon system for bread sale; the bread was ready for pickup at 7 every morning to a mainly European clientele. That’s how I learned English.” After matriculating in 1958, Ilias found work as a surveyor for the Pakistan government. The work took him all over East Pakistan, from Chittagong to Rangpur. In The World I Saw he charts his time as a surveyor-in-training: “After learning drawing and topography in the office at Tejgaon, I started my field training in the vacant lands located at Lalmatia and Adabor, which were later named as Mohammadpur.” But there were more important interests than land surveys: “Because I was an urban boy from an urban society, I decided to give up my training as a surveyor and joined the Dhaka Press Club. I was soon appointed manager.” There were three hour shows at Britannia Cinema, addas at Nawabpur’s Amzadia and Khush Mahal hotels and, above all, poetry and politics.